Participatory action research: tackling today’s complex challenges

Participatory action research (PAR) offers a practical and inclusive approach to tackling today’s complex challenges. By combining collaboration, critical reflection, and iterative cycles of inquiry and action, this approach helps create solutions that are both meaningful and sustainable. This post revisits the principles and practices of PAR, exploring its relevance in addressing interconnected issues like climate adaptation, biodiversity loss, and social equity.

Participatory action research (PAR) provides a valuable framework for addressing today’s complex challenges through collaboration, shared learning, and action for change. The concept of action research was first developed by Kurt Lewin in the 1940s, emphasising a cyclical process of reflection, action, and problem-solving. This was later expanded by Paulo Freire, who introduced ideas of empowerment and critical thinking, particularly in the context of adult education. As I noted in my 2016 blog, Participatory action research provides for multiple benefits, it is more than just a methodology—it’s a worldview that engages participants in iterative cycles of inquiry and action. In other pages on this website, I’ve also explored how PAR’s principles—collaboration, empowerment, and learning by doing—remain vital for addressing today’s interconnected challenges.

This post builds on those earlier reflections, revisiting the principles and practices of PAR in light of the changing challenges we see today. Over the years, including my 2001 thesis on collaborative environmental management, I have explored how PAR can drive meaningful social and ecological change. Technological advancements, an increased focus on equity and inclusion, and the urgency of addressing issues like climate adaptation and biodiversity loss have helped us better understand PAR’s potential to drive meaningful change. Here, I’ll explore PAR’s core principles, compare it with traditional scientific methods, and share some reflections on what I’ve learned along the way.

The core of action research

At its heart, participatory action research is guided by four interwoven principles that set it apart from traditional approaches. These principles help the approach stay participatory and impactful:

- Collaboration through participation – Engaging stakeholders at all stages of the research process ensures their insights shape outcomes.

- Acquisition of knowledge – Creating knowledge that addresses immediate problems and builds broader understanding.

- Social change – Addressing root causes to enable deeper, systemic transformations.

- Empowerment of participants – Building capacity so participants can address their own problems.

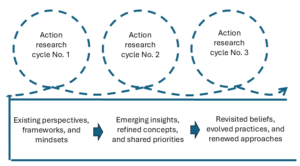

These principles form the backbone of PAR’s iterative methodology, which revolves around cycles of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting. This cyclical process ensures that solutions evolve dynamically, adapting to changing circumstances and new insights.

PAR builds on a long history of reflection and collaboration, practices that communities and cultures around the world have engaged in for thousands of years to address shared challenges and improve their collective wellbeing. These enduring traditions of working together to solve problems have provided the foundation for more formalised approaches to inquiry and action.

By the mid-20th century, Kurt Lewin introduced a structured framework for action research, emphasising reflection and problem-solving in iterative cycles. Paulo Freire later adapted these principles for adult education in Latin America, embedding empowerment and dialogue into the process. Their contributions continue to shape PAR as a methodology for driving social and environmental transformation.

The challenge of change and learning

Learning—especially when it means revisiting old beliefs or practices—can be uncomfortable. It often requires confronting uncertainties or admitting that previous approaches may no longer be effective. This discomfort is made harder by defensive behaviours in individuals and organisations—patterns that make certain topics “undiscussable” or create a gap between stated values and actions. For example, many groups may publicly commit to sustainability but struggle to have open conversations about the trade-offs or systemic changes this requires.

Critical reflection lies at the heart of addressing these challenges. Far from casual introspection, critical reflection helps people examine their assumptions, behaviours, and values, allowing individuals and organisations to navigate complex challenges more effectively. PAR weaves this reflection into its cycles of planning, acting, observing, and adapting, encouraging participants to question not only what is being done but why. By fostering critical reflection and addressing defensive routines, PAR builds trust and a culture of ongoing inquiry, essential for navigating today’s complex challenges.

In practice, reflection in PAR often involves examining three interconnected elements: the content of the issues being addressed, the processes used to engage with them, and the underlying assumptions or values shaping these efforts. By considering not only what is being done (content) but also how it is being done (process) and why it is approached in a certain way (premises), PAR encourages a deeper level of thinking. This approach helps participants uncover blind spots and rethink goals or methods that may not serve the broader purpose of creating sustainable and inclusive solutions.

This is also where the concept of triple-loop learning becomes particularly relevant. PAR encourages reflection not only on actions (single-loop learning) and the assumptions guiding them (double-loop learning) but also on the deeper values and worldviews that shape those assumptions. For instance, a project might move from improving specific practices to rethinking the purpose and broader impact of those practices within their social or ecological context. This level of reflection supports a shift from transactional to transformative approaches, helping participants create solutions that are sustainable and adaptable.

Participatory solutions for sustainable change

Facilitation is essential in helping diverse groups work together in a learning-focused way, especially in complex fields like environmental management. Participatory action researchers serve as facilitators who work through challenges like bringing together diverse perspectives, managing power dynamics, and ensuring that participant voices are genuinely heard. Reflecting on one’s own biases and maintaining flexibility are critical for building trust and fostering collaboration.

PAR actively addresses power imbalances by involving marginalised groups in decision-making processes, challenging systemic inequalities, and ensuring diverse voices are heard. For example, involving underrepresented communities in climate adaptation enhances relevance and fairness. This participatory approach fosters dialogue between local government, industry, and Indigenous communities, creating solutions that are both adaptive and resilient.

New technology has made PAR more accessible. Tools like participatory GIS, mobile data collection apps, and remote sensing support more inclusive participation by making data collection and visualisation more accessible to communities. These technologies allow for real-time feedback and adaptive responses, supporting dynamic management strategies. For example, integrating survey data with participatory mapping can deepen understanding and ensure that solutions are both evidence-based and grounded in lived experiences. Virtual collaboration also enables broader stakeholder involvement, ensuring diverse voices are included. By addressing power dynamics, PAR supports Just Transition principles, managing social, cultural, and economic changes fairly.

Learning by doing

In an age where people are rightly questioning top-down approaches to environmental management, PAR’s focus on learning by doing is more relevant than ever. Active participation in the research process helps people adapt their actions based on real-time feedback. This reflective process encourages thoughtful action and ongoing improvement, key to tackling complex, changing problems.

PAR is an important tool for supporting both adaptive management and co-design processes. Each of these relies on cycles of action and reflection to refine strategies over time. Adaptive management, which values flexibility, benefits from PAR’s reflective cycles that adjust strategies in response to environmental changes. For example, managing a freshwater catchment may involve adjusting practices based on new water quality data, keeping decisions relevant. Reflection supports cycles of planning, acting, observing, and adapting, encouraging participants to question not only what is being done but why.

Similarly, co-design invites diverse stakeholders to shape solutions, often where technical and social factors intersect. PAR strengthens co-design by promoting inclusive problem-solving, encouraging participants to review and refine ideas continuously. This approach is useful in urban planning, where residents, planners, and businesses collaborate to create shared spaces that reflect community needs. PAR allows these projects to evolve as participants reflect and adapt their designs.

By connecting PAR’s reflective steps with adaptive management’s flexibility and co-design’s inclusiveness, environmental management initiatives can create solutions that are both robust and responsive to the needs of all stakeholders. This integrated approach ensures that strategies remain adaptable, inclusive, and grounded in real-world contexts.

Comparing action research with mainstream science

While PAR and mainstream science can complement each other, their approaches differ significantly. While mainstream science often observes and explains, PAR functions as a science of practice—focused not just on understanding ‘what is’, but on co-creating ‘what could be’. This approach enables PAR to directly support social and environmental solutions through shared, practical inquiry. The table below summarises these differences:

| Aspect | Mainstream science | Participatory action research |

| Value orientation | Aims to be value-neutral | Value-driven, addressing socially and environmentally significant issues |

| Researcher role | Detached observer | Participant-observer, engaging with participants to create solutions |

| Facilitator role | Often absent | Central to the process; guides collaboration, reflection, and shared learning |

| Focus of inquiry | Describes and explains “what is” | Explores and co-creates “what could be” |

| Approach to complexity | Simplifies by isolating variables | Embraces complexity, considering social, cultural, and ecological factors |

| Research design | Pre-planned and structured | Emergent and adaptive, evolving based on findings and context |

| Learning process | Single-loop learning, for problem-solving | Double- and triple-loop learning, questioning assumptions and values |

| Generalisation | Broad, universal conclusions | Context-specific insights and solutions |

While PAR and mainstream science may differ in focus and methodology, they can complement each other to address complex challenges. PAR often integrates qualitative methods, such as participatory mapping and stakeholder interviews, with quantitative tools like surveys and environmental modelling. This mixed-methods approach makes sure solutions are backed by evidence and real-world experience. By combining the rigour of mainstream science with the adaptability and inclusivity of PAR, researchers can co-create practical solutions tailored to specific challenges solutions that tackle local problems while keeping the bigger picture in mind”.

Broadening the scope of action research

Looking back at the principles explored in this post—and reflecting on earlier discussions like my 2001 thesis chapter—it’s clear that participatory action research (PAR) is still a key approach for today’s connected challenges. Its core values of collaboration, critical reflection, and shared learning continue to resonate, even as the context in which PAR operates evolves. The urgency of addressing issues like climate adaptation, biodiversity conservation, and social equity has deepened our understanding of how PAR can drive meaningful, context-sensitive change.

From its foundations in participatory methods to its integration with adaptive management and co-design, PAR has demonstrated its strength as a flexible and iterative process. Its flexibility allows solutions to be created together and improved over time, so they stay useful and effective as things change. Practitioners can employ diverse methodologies such as appreciative inquiry, outcome-based evaluation, and deliberative dialogue. A wide range of tools, including stakeholder analysis, systems mapping, and SWOT analysis, can also be tailored to suit specific contexts and challenges.

Applications of PAR encompass fields like environmental management, healthcare, agriculture, and climate change. In each, PAR’s collaborative framework creates space for diverse perspectives and local ownership, enabling robust and sustainable solutions. For policymakers, PAR offers a way to connect local community efforts with bigger policy goals, particularly in resource-limited contexts. Its iterative nature also supports scalability, making it a valuable tool across local, regional, and sectoral levels.

PAR’s enduring relevance lies in its ability to bring people together to co-create solutions that are flexible, inclusive, and responsive to complex challenges. By integrating reflection, collaboration, and shared learning, PAR continues to empower communities and foster sustainable change.

More resources can be found from the main LfS participatory action research page. More links to related material can also be found from the LfS adaptive management page, systemic co-design page, and the Social Learning and the Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation sections.

An independent systems scientist, action research practitioner and evaluator, with 30 years of experience in sustainable development and natural resource management. He is particularly interested in the development of planning, monitoring and evaluation tools that are outcome focused, and contribute towards efforts that foster social learning, sustainable development and adaptive management.

Leave a Reply